On 29 August 2003, a massive car bomb killed the Iraqi Shia cleric Ayatollah Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim in the holy city of Najaf, along with 85 others. The attack, four months after the US-led invasion and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, was carried out by Sunni militants. The assassination echoed across a Middle East still in shock at the destruction of an Arab regime by western arms.

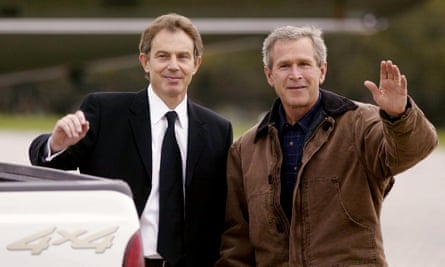

Horror piled upon horror over the following years. In February 2006, al-Qaida in Iraq, recently founded by the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, blew up the golden-domed al-Askari mosque in Samarra. The wider target was the country’s Shia majority, elated by the removal of the hated Sunni dictator. Next door, the Islamic Republic of Iran was celebrating the demise of its enemies – the Baathists of Baghdad and the Taliban in Kabul – courtesy of George Bush and Tony Blair.

And then, on 30 December 2006, Saddam was hanged. As he stood on the gallows, men in ski masks taunting him with Shia slogans, he denounced them contemptuously as “Persian dwarves”. Blurred video footage of his final moments was viewed by millions of Arabs – unleashing both fury and praise for his courage in the face of death. The timing, just as Sunnis were celebrating the Eid al-Adha holiday, added insult to injury. The rest is not only history but the current reality of a dangerous and deeply unstable region.

Now, as the British government faces intense public scrutiny from the Chilcot report, the war continues to cast a long shadow over Iraq, the Arab world and beyond. Even at the time, in the face of bitter controversy and mass protests, it was seen as a pivotal event. That judgment has been repeatedly confirmed by its toxic and destabilising legacy – the spread of hateful sectarianism, the growth of al-Qaida and then Isis, the empowerment of Iran: all were the unintended but undeniable consequences of 2003; all, like the latest carnage in Baghdad, are still making headlines today.

Arab and western analysts and historians are in broad agreement on these points. Hindsight naturally helps, though some spoke out at the time of the risks involved in the war – and were ignored. “People did not think that al-Qaida and Iran would play the role that they did,” Blair told the inquiry. Chilcot however, stated clearly on Wednesday: “The risks of internal strife in Iraq, active Iranian pursuit of its interests, regional instability, and al Qaida activity in Iraq, were each explicitly identified before the invasion.”

On another related issue, sometimes used to try to justify the invasion, few see any direct link between the fall of Saddam and the later uprisings of the Arab spring, which toppled four other dictators but left many in place, unscathed and more ruthless than before.

And, bringing a bleak story up to date, most experts argue too that the current crisis in Syria – the bloodiest of our times with 400,000 dead and millions made homeless – has been heavily, and negatively, influenced by the events of 2003 and after.

In the wake of the Iraq war, intervention became a dirty word, at least in the west – and arguably to calamitous effect. “It’s the ghost of Iraq that stops Barack Obama intervening overtly in Syria,” says Toby Dodge, of the London School of Economics.

Emile Hokayem, of the International Institute of Strategic Studies, agrees: “Iraq is seen by many as the original sin, and for understandable reasons. People read what they want into the tragedy. It is indeed a massive tragedy. It permeates everything, the way we talk about politics. It is pervasive.”

Back then, the head of the Arab League, the Egyptian politician Amr Moussa, warned memorably that an invasion would “open the gates of hell”. Reservations like that were not out of love for Saddam – his “republic of fear” was a byword for cruelty at home and aggression abroad – but out of anxiety about who, and what, would follow him.

For Hayder al-Khoei, an Iraqi-British academic, Saddam’s domain was already “hell” because of his brutal repression and the ravages of a decade of western sanctions. The weapons of mass destruction (WMD) issue was barely relevant. But the war meant, above all, the replacement of a Sunni regime by a Shia one. “That was an earthquake for the region, and the tremors and recriminations are continuing,” he argues. “And the fact that it was a cowboy from Texas who overturned a 100-year-old status quo was insulting. It was hard to stomach and psychologically difficult to deal with.”

Gilbert Achcar, a Lebanese professor at SOAS, London University, sees the invasion as a direct continuation of the unfinished business of 1991, when Bush senior left Saddam in power to crush the Shia intifada that erupted in the wake of his ejection from Kuwait. The US intervention – what he succinctly calls Bush’s “cakewalk into an Iraqi quagmire” – created the conditions for both the raw sectarianism and jihadi violence that followed. “You didn’t need a crystal ball,” he sighs. “It was very predictable and what happened was exactly what was predicted.”

Aimen Dean, a Saudi who now works as a consultant in Dubai, has an unusual perspective – and rare inside knowledge. In 2003, he was an undercover agent for the British intelligence service MI6, having defected from al-Qaida as his doubts grew about its violent methods. “If Saddam is removed, a pillar of Arab nationalism will fall and it will only be replaced by Islamism on the Sunni or the Shia side,” he cautioned his handlers.

Events proved him right: after Saddam’s hanging, Salafis in the Gulf donated millions of dollars to fund al-Qaida’s war of bombings, beheadings and kidnappings against Shia “apostates”. Luay al-Khatteeb, an Iraqi scholar at Columbia University, believes the Sunni autocracies preferred these terrorists to a Shia democracy imposed by American power. “The invasion was not only shock and awe for Iraq, but a wake-up call for the region,” he has written.

“Virtually all of Iraq’s neighbours provided shelter, support and in some cases finances and training to different insurgent groups. Iraqi Baathists were able to organise attacks from the safety of Amman and Damascus, while some Gulf states either tolerated or oversaw funding for Salafist-jihadist groups.”

But Abdelkhaleq Abdulla, a political scientist from the UAE, holds the US and UK primarily responsible for giving a deadly boost to the takfiri extremism embodied by the psychopathic Zarqawi – and to his successor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, emir of today’s Islamic State (also known as Isis, or Daesh). “If it wasn’t for 2003, there would have been no Daesh,” he insists. “To blame it exclusively on Saudi Arabia or Wahhabism is to dodge the issue.”

Buthaina Shaaban, then and now an aide to the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, predicted “inflamed conflict” between Sunnis and Shias if Saddam was ousted. Assad’s mukhabarat – secret police – sent Syrian extremists across the border to join the Iraqi resistance to the Americans. In 2011, he crushed initially peaceful protests and released jihadis from his prisons so they would militarise the uprising and make it easier to fight.

Iran condemned the invasion but took advantage of its aftermath and gloated when Saddam was killed. “Iran was sucked into this conflict without wanting to get involved,” insists Foad Izadi, of Tehran University. “The Americans carved out a role by playing on Sunni-Shia tensions. We did not benefit.” Tehran’s enemies watched apprehensively.

“Iran won twice, first in Afghanistan and then in Iraq,” recalls Sima Shein, at the time a senior official with Israel’s Mossad spy agency. “The moment Saddam was gone, the Shia came out on top and the Iranians won a strategic victory.”

The American architects of the war defended their vision, even after the catastrophic disbanding of the Iraqi army in May 2003 – widely seen as the greatest blunder of the post-war period. Neoconservative ideologues came up with a spurious “domino theory” according to which regime change in Iraq would be emulated elsewhere and even somehow promote recognition of Israel by the Palestinians and moderate Arab states. “Baghdad is for wimps, real men go to Tehran,” went the (half)-jokey Washington saying.

In 2005, the US hailed regional changes it attributed in part to the removal of Saddam: one was the cedar revolution in Lebanon, where mass protests erupted after the assassination of former prime minister Rafiq al-Hariri, a Sunni with close Saudi links, and culminated when the Syrian army withdrew after a 30-year occupation.

Condoleeza Rice, Bush’s secretary of state, talked up “democracy promotion” that arm-twisted a reluctant Hosni Mubarak to hold parliamentary elections in Egypt, and even the Saudis to allow municipal polls. “How much credit went to Iraq, how much to the internal dynamics of each country and how much to luck depended on whom you asked and what position he or she wanted to justify,” wrote George Packer in The Assassins’ Gate, his fine study of US policy.

US claims, never convincing, have not stood the test of time. “It is utter bullshit in any way to link the Arab spring to Iraq as the neoconservatives do,” says Dodge. “What causal link could a quasi-imperial failed invasion of Iraq have to mass popular uprisings?” Toppling Saddam’s statue in Baghdad’s Firdaus Square made for a great if stagey photo opportunity. Its fall may indeed have “demystified the power of dictatorships that had hitherto seemed eternal and unbreakable,” in the words of Nadim Shehadi of Chatham House. But the changes that followed elsewhere were caused by more underlying factors, some of them also visible in Iran in the “Green” protests that erupted after the “stolen” presidential election in 2009.

Iraq’s turmoil continued to affect the wider region, and to be affected by it, even as attitudes to the occupation shifted. “In the early years you had strong anti-US resistance among the Sunnis but after 2006-7, with the civil war and defeat of al-Qaida, Sunnis came to see the Americans as the lesser evil to Iranian domination,” notes Achcar.

The ultimate irony came in 2010 when Tariq Aziz, Saddam’s veteran foreign minister, accused Obama in a Guardian interview from his prison cell of “leaving Iraq to the wolves” by pressing ahead with a withdrawal of US combat troops in the face of continuing instability.

Libya’s uprising, after those in Tunisia, Egypt and Bahrain, stirred the ghosts of Iraq. Ordinary Libyans fought to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi while Nato’s air campaign, driven by Britain and France while Obama “led from behind”, was coordinated with Arab Gulf allies who backed rival rebel groups. It fuelled another angry but inconclusive debate about how to respond to the Arab spring. The aftermath has not been kind to Obama’s reputation or the credibility of US power in the Middle East.

“In a way, the US-British invasion of Iraq was the unintentional catalyst for a lot of these regional transformations,” argues Hokayem, who did not support the war but is a fierce critic of vacillating US responses to Syria compared to the strategic approach taken by Iran and Russia. “They would have probably occurred in one way or another as these weak, repressive and incompetent Arab governments were already there. But the invasion was an enabler. And there is a clear link between 2003 and the second age of jihadism and sectarianism. Westerners did not create these destructive phenomena but the invasion exacerbated them decisively. That’s an important distinction.

“People talk about the Iraq war the way they want to talk about it. There are a lot of self-serving arguments. The hypothetical scenario I and others are struggling with is this: let’s imagine that tomorrow Assad survives in the same way Saddam survived in 1991. If there is then a semblance of internationally-accepted ‘stability’ in Damascus, would I, five years down the road, advocate another intervention in similar circumstances? The Iraq war fundamentally changed our collective view of what is feasible and desirable and the constraints that policy makers operate under.”

Debate about the Chilcot report will take place largely in Britain but it will likely be listened to far more widely. In the Middle East of 2016 perhaps only Kurds still view the war in a positive light – though in the words of Barham Salih, a leading Iraqi-Kurdish politician and deputy prime minister under Nouri al-Maliki, “Isis has demonstrated that the mission was not accomplished in Iraq”.

Another important promise failed to materialise. Part of the case for the invasion – “that action in Iraq could be made more palatable”, as Rice put it in her memoirs – was that it would be followed by an initiative to restart Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. Bush’s endorsement of the “road map” for peace was seen as a sop to Blair. The claim that impetus would be provided by Iraq has been described as “naive if not deliberately deceptive”. In any event, that map led nowhere slowly.

“The Iraq war is going to affect this part of the world for many generations to come,” concludes Izadi. “It shows what happens when you invade a country and don’t think carefully – when you have a president like Bush in the US and someone like Blair, who should have known better given the long history of British involvement in the region and the disasters that were caused by the colonial powers.”